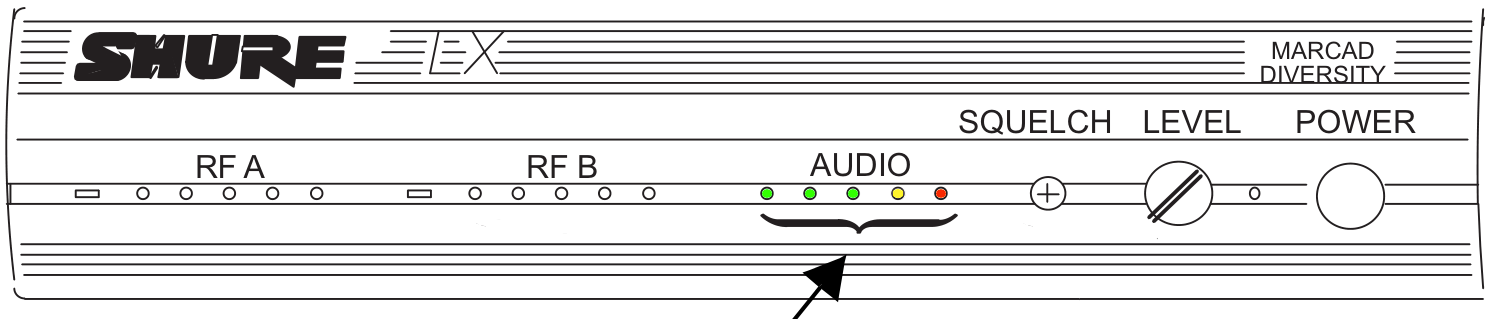

Above: Stereo VU meter and headphone controls in the master section

To use the stereo VU meter and headphones to good advantage, first make sure that all the

pre-fader listener (PFL) and after-fader listener (AFL) buttons are up. These PFL and AFL

buttons are near every fader and near every master "send" in the master section. On the

Alan & Heath GL2400 mixer if a button is round (not square or rectangular) it is a PFL

or AFL button. All these round buttons need to be up to start with. All their associated

yellow LEDs must be extinguished. Additionally, just below the stereo VU meter in the master

section of the mixer board there is a red LED labeled PFL/AFL. This LED must be extinguished

also. If it is illuminated, there is a PFL and/or AFL button down and a yellow PFL or AFL

indicator still illuminated somewhere.

Now press the single PFL button for the channel you want to gain trim. The yellow LED

near the PFL button should light and the red PFL/AFL LED under the main VU meters should light.

The stereo VU meter is now monitoring that channel's gain trim, and that channel only. Adjust

the gain trim and if necessary, the line-pad switch, for maximum green with no yellow or a

rare yellow flicker. While you are doing this, you will be able to hear that channel, and

that channel only, in the headphones. Perhaps the headphones are too loud or soft for

your taste when the gain trim is adjusted correctly according to the stereo VU meter. The

headphone MONITOR knob (red) below the stereo VU meter is just for you. Adjust that to your taste.

It has no effect on the signal strength anywhere in the mixer board, except for the amount

of signal that is sent from the stereo VU meter to your headphones.

After you have gain-trimmed a channel using the stereo VU meter, let that channel's PFL button

up again and observe that the PFL/AFL red LED is extinguished again. The stereo VU meter

and the headphones now default to monitoring either the L-R buss or the recording mix

(also known as the 2TRK mix), as selected by the small white button just below the headphone

MONITOR knob. In our situation the need to monitor the L-R mix in the headphones is rare

because the overall sound balance in the sanctuary can be much better evaluated by

listening to the room without headphones. Why use technology when there is a more perfect

way to monitor that sound? Thus, for all practical purposes the white square button below

the headphone MONITOR knob should always be down so that the headphones and the stereo VU

meter monitor the recording (2TRK) mix by default.

Alan & Heath—Creating the L-R mix

The L-R master faders (two left-most yellow sliders) are the overall volume controls for

every destination. If you raise this above 0 dB the sound will get louder everywhere—

in the sanctuary, in the nursery, in the hearing loop, on the Facebook stream, and everywhere.

Likewise, if you lower this below 0 dB the sound will get softer everywhere. There is

one exception: Sounds in the recording mix that arrived there only via the Aux 5 and 6

sends will not be affected by the L-R master faders. (the L-R master faders have no

authority over channels that have all the L-R, 1-2, 3-4 couplers up.)

Once all the channels are properly gain trimmed (red knobs at the top of the mixer board)

then most of the rest of the gain structure falls into place much more easily. Furthermore,

most mixer boards are designed with extra gain margins on the intermediate points in the

mixer board, so even if there is a minor gain structure error in the middle of the chain

it will create little or no distortion or hiss or hum. The discussion that follows assumes

that each channel is properly gain-trimmed.

At the beginning of any event, set the yellow L and R faders to 0 dB. The nominal

setting for any master fader should be 0 dB.

For the moment, assume that no groups are being used and the L-R (yellow) faders are

at 0 dB. For each channel that has a signal that should be present in the main mix (sent

everywhere--sanctuary, fellowship hall, nursery, Facebook stream, recording—everywhere)

press down the white "L-R" button near the associated channel fader (black slider). Then

push the channel fader (black or blue) up to near the 0 dB line. In the example of the

pastor's sermon, there is only one microphone that has a significant amount of signal, the

pastor's microphone. For a properly gain-trimmed channel, 0 dB represents a nominal mix,

so usually you will find that a pleasing mix will be found with the faders near 0 dB, plus

or minus a bit to suit your judgement.

The gain structure challenge now is to be sure the L-R busses have nominal levels of signal

on them when the L-R master faders (yellow) are at 0 dB. Above the L fader (left-most

yellow slider) you will find an AFL button. Press it down and look at the stereo VU

meter. It should be bouncing up to at least –12 and no higher than 0 dB. (Be

sure no other PFL or AFL buttons are down. The meter is only accurate when exactly one

PFL or AFL is in use.) Good gain structure on the L-R busses will almost automatically

happen if the channel gain trims are correct, so it is not urgent to keep monitoring

this. But if you suspect a problem, this is one place to check. Check each of the

L and the R channels individually and one-at-a-time. If signal levels are too high,

pull down about the same amount on all the channel faders (black), and push

up if the signal is too low.

You will probably notice that as more and more channels are opened up with significant

signals on them, you may need to lower the channel faders (black) to prevent the L-R

signal levels from going into the yellow (going above 0 dB).

For example, in a praise and worship team situation you might have four vocalists with

microphones, a guitar, a piano with two microphones on it, a cello, and a flute, all with

mics. Now if each of these are properly gain trimmed and if each channel is coupled to

the L-R busses, and if each channel fader is set at 0 dB, there will be more than

0 dB, maybe +6 dB or so on the L-R busses. This happens because of the multiplicity

of signals flowing onto those L-R busses. Just like a river with many tributaries gets

wide, the L-R busses with many signals flowing into them can get overloaded. But if you

just pull back all the channel faders (black) to a little below 0 dB, the sum of all

their signals will end up being close to 0 dB on the L-R busses. Fortunately, our

Alan & Heath mixer has lots of headroom (+16 dB according to the user's manual),

so gain structure errors do not become very noticeable on these mix busses, and it

is OK to run the L-R busses with yellow VU levels (up to about +6 dB). But for the

very best results try to run te channel faders a little below 0 dB if many faders

are up, thus keeping the L-R bus in the green, near or just under 0 dB.

Alan & Heath—Creating group mixes.

If you elect to use groups, Let the channel L-R coupler up and put the 1-2 or 3-4 button down.

Now that channel is coupled to either the 1-2 stereo group or the 3-4 stereo group.

Usually only one (or zero) of these three coupler buttons should be down for each channel.

(In our context, pressing two or more of these on one channel will probably create

complications in balancing out the mix.) The group busses can be checked for proper

signal levels just like the L-R busses. Press down one of the AFL buttons above a

group fader (red slider) to check that signal. Similarly, if corrective action is

needed, all the channel faders coupled to that group need to be adjusted in unison.

On Covenant Church's mixer, the group faders (red) are set up in stereo pairs to send

their signals to the L-R mix. Groups 1 and 3 send signals to L. Likewise, groups

2 and 4 send signals to R. This is controlled by a set of four pan-pots (brown) and

switches (white pushbuttons) located above the group faders (red) in the master section

of the mixer. Normally we find no need to change these pan-pots and switches.

Group pan-pots 1 and 3 should be full counter-clockwise and group pan-pots 2 and 4

should be full clockwise. (Pan-pots are color-coded brown on our mixer.) The four

white square "GRPx TO L-R" buttons located near each group pan-pot should be down.

Alan & Heath—master outputs.

Sanctuary mix master

After the main mix is created on the L-R busses we route that to various places using

outputs from the master (middle) section of the mixer board. The Sanctuary mix is

derived by mixing the L-R busses equally into one monaural mix. This output is controlled

by the "M" fader (yellow) in the master section. Normally this should be set at 0 dB,

but if you want to make it louder or softer in the sanctuary, this is the overall "program

volume control" for that purpose. Why might you want to do this? Maybe the sound system

is being used for an event that is happening exclusively in the fellowship hall. Then

by sliding this "M" fader all the way down the hollow echoey distant sound of the sanctuary

speakers will not bleed into the fellowship hall. You can monitor this gain structure

of this output using the AFL button just above the "M" fader.

Fellowship hall mix master

Another master output is from the bottom of the "matrix" section in the top left area

of the mixer. The fellowship hall mix has the L-R busses and some of the AUX 5

augmentation of the recording mix added into it via the "EXT IN" (grey)

knobs at the top of the matrix area of of the master section. The AUX 5-6 augmentation

is added to support congregational singing for those seated in the fellowship hall.

This mix is also delayed about 65 ms via processing in the power amplifier for this

channel. This delay puts the sound in time-synchronization with sound arriving in

the fellowship hall from the main speakers located over the pulpit area. The "MTX1"

fader (red knob) is the master gain for this output. Normally we set this at

0 dB (3 o'clock), but if you want to adjust the loudness in the

fellowship hall only, this is the "program volume level" knob for that.

Basement mix master

Another master output is from the bottom of the "matrix" section in the top left area

of the mixer. This mix is similar to the fellowship hall mix (L-R + AUX 6) although it can be

independently adjusted for even more support of congregational singing since the

basement areas will have no acoustic sound from the sanctuary in them. We have speakers in

the nursery, the basement hallway area outside the nursery, and the youth room. The

"MTX2" master is the "program volume level" knob for these speakers. Normally we set this

at 0 dB (3 o'clock). Each of the loudspeakers in the basement has an independent

volume control on them as the final program volume level adjustment. Anybody listening

via these basement speakers is allowed to adjust the volume controls on the loudspeakers

so that the volume suits their taste.

Stereo recording mix masters

Finally, in the master matrix section, "MTX3" (left) and "MTX4" (right) provide a stereo output

for the Facebook stream, the CD recorder, and the hearing loop system. The stereo recording mix is

composed of the L-R stereo signal plus the AUX 5-6 stereo signal which gets added in

via the EXT IN (grey) sends a the top of the matrix section. The "MTX3" or

"MTX4" master outputs can be checked for gain structure by pressing an AFL button near

the "MTX3" or "MTX4" master knobs (red). Then the stereo VU meter will show the level at

this output and the headphones will allow you to listen to this signal. Normally we set

these "MTX3" and "MTX4" masters at 0 dB (3 o'clock).

This stereo recording mix from MTX 3-4 outputs of the matrix goes to the RANE (brand) distribution amplifier where

there are a number of additional gain settings and outputs. The RANE distribution amplifier

is set up such that if you send it properly gain structured recording mix, all the signals within

the RANE unit will also be properly gain structured as well as all the signals delivered

from that unit to other devices such as the Facebook stream, the hearing loop, and the

2-TRK monitor in the Alan & Heath mixer, the CD recorder, and any other outputs that may

be connected to the RANE distribution amplifier. One stereo output from the RANE distribution

amplifier, containing the final stereo recording mix, is routed back to the Alan &

Heath mixer via the "2TRK" input to the mixer. This allows the final recording mix to be

the default monitoring heard in the headphones and it also allows the Alan & Heath's

stereo VU meter to monitor the final gain structure of the stereo recording mix at the

outputs of the RANE distribution amplifier.

If any of these master outputs are showing signals that are too strong or two weak it is

quite unlikely that these masters are the best places to make the adjustment. The most

likely culprits are channel gain trims that have not been carefully set and/or inappropriate

levels on the L-R busses due to a mix that is overall to strong or too weak (Too many black

faders too high or too low with a half-dozen or more channels in the mix).

A bit off-topic: Gain structure of the recording mix

For a variety of reasons, if all channels have been properly gain-trimmed and a reasonable

mix is in progress, the VU levels of the recording mix (2TRK) will take care of themselves

and land in –3 to –12 dB range rather naturally. Thus, monitoring the VU levels

of the recording mix is not a priority. However, listening in the headphones to the

recording mix is a good thing to do periodically to assure that the recording mix is well-balanced.

The recording mix normally will track the sanctuary mix, but the AUX 5 and AUX 6 sends

are used to add additional signal to the L-R mix, thus creating the recording mix. This

is necessary for two reasons: 1.) In the sanctuary the musical portions of a worship

service are usually significantly louder than the spoken-word portions. But at home,

listening on the Facebook stream, this loudness variation would be obnoxious. In the

recording mix we need to elevate the loudness of the spoken-word portion of the

worship service to match the loudness of the music. Also, 2.) in the sanctuary there are

such things as congregational responses. Normally that is singing and responsive reading,

but these sounds also includes reactions such as laughter if the pastor makes use of humor,

and just the general sound of the room. Also, some musical instruments are not mixed into

the L-R mix because they have enough acoustic energy to not need reinforcement. The organ,

piano, and drums would be typical examples. These aspects of the sound in the

sanctuary need to be added to the recording mix to make it sound natural. The AUX 5

and AUX 6 busses are used to augment the L-R mix and thus create the recording mix.

Normally the AUX 5 and AUX 6 sends (Yellow knobs that are above brown knobs) should

be off (fully counterclockwise--no augmentation of that channel in the recording mix).

There are two exceptions.

Exception 1.) Spoken word, AUX 5 & AUX 6 each to 2 o'clock

If a channel has a spoken-word signal on it, then turn each of those AUX 5 and AUX 6

sends to the 2 o'clock position to couple an extra amount of that signal into

the recording mix. This is done to bring the spoken-word part of the worship service

to the same overall loudness as the musical parts of the service. Musical

vocal parts and instruments like guitars that are being amplified should not have extra

signal coupled into the recording mix. They are going to be plenty loud in the

recording mix because they will be strongly present in the L-R mix. Only spoken-word

parts get augmented. Sometimes praise and worship leaders have spoken-word parts.

Ideally, these channels should be augmented when there is speech and not augmented

when there is singing. But this back-and-forth adjustment of AUX 5-6 senders is too

much workload so usually they do not get augmented. If at all possible, have the

praise-team leaders walk to a different mic such as the podium mic for spoken word

parts of the worship service.

Exception 2.) Miking of a musical source for the recording only

It is also possible to couple a signal only into the recording mix. We usually do this

with the organ, piano, choir, and the ambience channels. (Channels 23 and 24 are the ambience

channels, other mics may be used in other channels as needed.) For channels contributing

only to the recording mix, leave the L-R, 1-2, and 3-4 buss coupler buttons near the

associated faders up. Those signals now cannot get into the L-R main mix

nor will they be reproduced in the sanctuary loudspeakers. But by adding an extra

amount of them to the recording mix via the AUX 5 and AUX 6 sends (yellow knobs) these

signals can still be mixed into the recording mix. To add from one channel in mono to

the recording mix, turn AUX 5 and AUX 6 each to 2 o'clock on that channel. Very often

we use two microphones for these types of signals and mix them in stereo. To add from

a stereo pair of channels into the recording mix turn the channel that will be the "left"

channel's AUX 5 fader to 3 o'clock and leave the AUX 6 fader off. For the channel that

will be the "right" channel, turn the AUX 5 fader off and the AUX 6 fader to 3 o'clock.

The AUX 5-6 busses are set up "post fader" so the normal (black) channel faders have

authority over AUX 5-6 in their channels even though the L-R, 1-2, and 3-4 couplers

are all up. (Normally the black slider-faders have no authority over AUX sends.)

Thus, after setting up the AUX 5-6 sends, just use the main black faders in the ordinary

way from that point onward to blend these sounds into the recording mix.

Power amplifier gain controls

Each power amplifier has its own gain control. These are set to provide the desired

overall maximum loudness achievable at the loudspeakers (or other loads) that the

power amplifier drives. Sometimes VU meters are provided to show the power output

levels that are transpiring. Whereas maximum green with no red showing on a VU

meter is the usual goal, this is not the goal on a power amplifier. Red is still

to be avoided, but any amount of green, including no green, is acceptable for a

power amplifier. At this point there is no need to overcome electronic noise.

Speaker inputs are not susceptible to radio signals and other interference so the

drive to the loudspeaker can be whatever sounds good without overloading the

amplifier (without driving the amplifier's VU meter into the red) and without overloading

the loudspeakers. At Covenant

Church we have four channels of power amplification. (This discussion ignores

the monitor channels. That's another topic for another day.)

[Side note: There is a different strategy that can be used for setting the gain

structure of a power amplifier. This one is arguably the more professional choice,

and is typically what is done in large venues, such as a rock concert with over

1000 people attending. But but practically, the professional technique can result

in ear-splitting unpleasant loud howls and buzzes and even speaker blow-outs when things

go wrong such as uncontrolled feedback or a guitar plug that is half-way inserted.

That is why we do not use this strategy at Covenant Church. The "professional"

strategy is to send some test program material out of the mixer board and into

the power amplifier and use the mixer's main VU meter to set that AFL output level

to bounce up to 0 dB at the peaks, possibly with a little yellow flicker at times.

Then use a portable meter (e.g. a DMM) to monitor the output voltage level of

the amplifier and increase the gain control on the amplifier until the power

level sent to the loudspeaker matches the loudspeaker's power specification. This

allows the speaker to be driven to its full rating at will by the sound-board

operator. That level might be even 130 dB SPL—because large amplifiers and speakers

can do this! That level is literally painful if hearing protection is not used.

This also requires engineering calculations to determine the correct voltage level

in this amplifier's context relative to the power specification of the loudspeaker.

Then in normal use the mixer's master output fader for this amplifier is typically

operated somewhat below 0 dB, say at -10 or -20 dB, unless really loud sounds are wanted.

(The amplifier's power output specification must be sized appropriately relative to

the loudspeaker for this technique to work well. Typically the amplifier

will be rated at about twice the power of the loudspeaker and not more than five times

the rating of the power amplifier.)]

Any power amplifier's input level can be monitored at the Alan & Heath's stereo

VU meter via the AFL button on the mixer board for that signal's master fader.

Remember, any amount of green including no green is acceptable. We just don't

want to see any red. If the signal is bouncing into the red, that is a gain

structure error and needs to be fixed at that master fader (turn it down) or

perhaps in the signal chain leading up to that master fader. If the signal

at this point is nearly bouncing into the red and it still is not loud enough

in the room, that is also a gain structure error. This type of error needs to

be fixed via the gain controls on the power amplifier for that signal.

Crown CDi1000 power amplifier—Sanctuary

This amplifier is located in the rack below the sound desk. It actually contains

two channels. This paragraph is about the channel that drives the sanctuary

speakers. The signal arriving at the input of this amplifier will have its peaks

typically bouncing up to about –12 dB or as much as 0 dB on the very loudest

sounds, assuming proper gain structure all the way back through the mixer board to

the source. (The input level to the power amplifier is the AFL level from the "M"

(yellow) fader on the mixer board.) The front-panel gain control here should be

adjusted when a loud event is in progress, the loudest sounds ever desired from the sanctuary speakers. Adjust

this knob to produce the desired loudness in the room, or a bit more for some margin.

That's it. As long as red clipping indicators are not blinking (and assuming the speakers can take the power)

everything is good, regardless of where the VU meter on the face of the power

amplifier is bouncing, so long as it is not bouncing into the red. In our sanctuary

this knob is taped down at about 10 or 11 o'clock because it NEVER needs

to be adjusted. If you want louder or softer sound in the sanctuary (only modifying

the loudness in the sanctuary), use the yellow "M" fader on the mixer board for that.

Normally, set the "M" fader (yellow) to 0 dB. Only adjust if that is not producing

the right loudness. If that is not enough, push up the L-R faders too, but seriously,

if pushing up the "M" (yellow) fader all the way is not enough, check for a gain

structure error earlier in the signal chain first.

Some power amplifiers, including our Crown power amplifier, have other ways of

controlling maximum loudness. Our amplifier is set up with a maximum power output

limit of about 60 watts. (Our sanctuary is very lively-sounding. We do not need

much audio power to make the sound objectionably loud—60 watts is plenty.)

This is to protect the loudspeakers in case of a prolonged burst of feedback howl,

or a loud buzz such as can happen if a guitar's signal-cord comes about half-way

out of its socket. There are also fuses inline with the speaker wires at the back

of the Crown power amplifier to provide yet one more layer of protection in case for

some reason the Crown amplifier might boot up in some configuration without the

60 W power limit. Limits like this can save on heartache later!

Crown CDi1000 power amplifier—Fellowship Hall

This is the same amplifier box that drives the sanctuary. The other gain control sets

the maximum achievable loudness in the fellowship hall. Everything in the paragraphs

above about driving the sanctuary speakers applies here except that if you want to

adjust the volume level in the fellowship hall, use the MTX1 master fader (red knob,

near the bottom of the matrix section in the master area of the Alan & Heath mixer).

Once again, this fellowship master fader should be set at 0 dB (3 o'clock) normally

and you should only adjust that if it is not producing the volume level you want.

Bogen CT100B power amplifier—Basement Loudspeakers

This amplifier drives several speakers in the basement including the nursery and the

youth room. Each of these speakers in the basement has its own volume control, a

passive rheostat. (Most of these rheostats are burned up and difficult to set. This

happened on account of turning this power amplifier up too high in the past.) This

power amplifier is really an "integrated amplifier" that we are using only for its

power amplifier (and equalizer). This "integrated" amplifier has its own mixer,

which must be properly gain trimmed as any mixer would be. After that there is a

master volume control. With all the basement speaker rheostats set to full volume,

this master volume control should be set to provide the loudest desired sound in the

rooms in the basement. Then the loudness of each speaker in the basement can be

adjusted to suit the taste of those nearby by turning down the rheostats.

Bogen GTS100 power amplifier—Hearing Loop

This amplifier drives a hearing-loop

antenna that is embedded in the ceiling of the basement and drives a signal up into

the sanctuary (and down into the basement for that matter). This hearing loop signal can be

directly received by hearing aids that are equipped with a telecoil. The signal

levels in this system should conform to international standards. To achieve that

a VU meter (actually a salvaged meter re-purposed) has been set on top of this

amplifier to monitor the hearing loop signal. When the meter is bouncing up to

half-scale the signal is at the ideal standard level. It is acceptable for the

meter to bounce up just a fifth of the way or all the way. Hearing aids will be

able to adapt to this much change of signal level. It is best to let the hearing

aids do that adaption rather than take your time to fuss with this. However if

the hearing loop signal is routinely pegging the meter at the maximum, turn the

master fader on this amplifier down a bit. Likewise, if the meter is not making

it at least a fifth of the way up-scale on normal programming, turn the master

up a bit. If you make adjustments, make the minimum adjustment needed to

get the signal between 1/5 and all the way without pegging it. Do not work hard

to make it bounce up just half-way because probably the programming will change

(the song will end or the prayer will end) and then a large adjustment will be

seen to have been too much overall.

In pre-pandemic days perhaps a half-dozen to a dozen people used the hearing loop

each Sunday. For a few of these people this is the difference between

understanding almost every word spoken and missing over half of the words spoken.

Probably even people with normal hearing would find that listening to the spoken

word via the hearing loop would be more pleasing and relaxing and hi-fidelity

sounding than listening to the loudspeakers in the sanctuary. You also might

have noticed that the equalizer on the hearing loop amplifier is set to some

very extreme settings. This is to compensate for the inductance that is typical

of a hearing loop transmitting antenna. It does not have a flat frequency response,

so we make up for that with the equalizer on this amplifier.

A final remark on power amplifiers

You may have noticed that all of our power amplifiers are over-powered for our

needs. This is typical in any installation. Due to sales, marketing, availability,

and other issues, oversized power amplifiers happen. Our sanctuary for example,

can be driven loud enough for our needs by a 60 W amplifier. But to require that

the amplifier be exactly 60 W would needlessly narrow the available choices

and thus raise the cost of purchasing an amplifier. It might happen that a

250 W per channel amplifier such as the Crown CDi1000 is on sale and

represents the best bargain. It is perfectly fine to have a (moderately) oversized

amplifier but an undersized amplifier will always be a problem. If there is at

least enough power from each amplifier, then each amplifier's gain control can

be used to match the amplifier's output to what is really needed.

This ends the discussion of gain structure. If you have questions or comments,

you may address them to the author of these pages, Douglas(dot)DeBoer(at)Dordt(dot)edu.

|

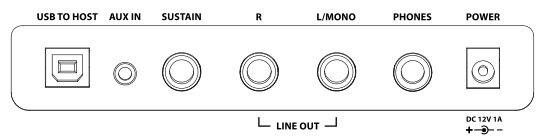

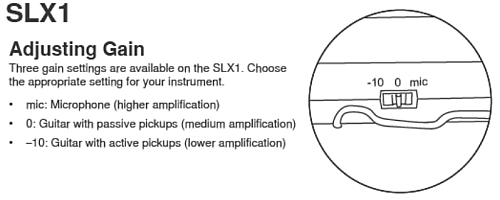

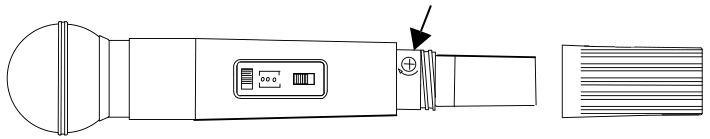

Above: Each gain adjustment has some type of indicator to help set it correctly.

Above: Each gain adjustment has some type of indicator to help set it correctly.